What just happened:

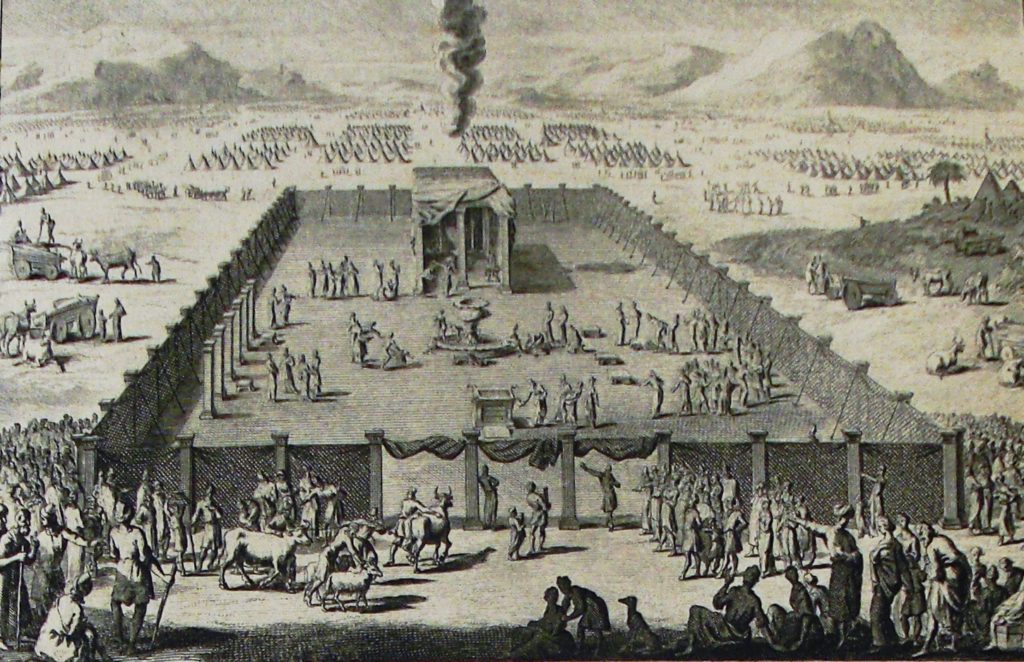

Leviticus opens with several laws of sacrifice and the details therein which are, let’s be honest, alarming for anyone who either likes pigeons or believes blood should be dashed on the wall rarely if at all.

And I thought to myself, Leviticus, your reputation precedes you. Because that’s pretty much what I know of this third book — that it’s a set of rules, rules and more rules, associated with the Levites.

For the first few pages of this section, I thought there wasn’t much in the way of a picture idea that I could glean. The pigeon thing threw me. And it was interesting to learn we aren’t supposed to eat fat. (Clearly no one told my grandma Lilly that because: schmaltz.)

But I didn’t see how I could use the above in my day to day. Then, pulling back, I did in fact glean a few things that perhaps I was taking for granted on first skim.

Of note:

- First off, there’s the embedded message that everyone sins — priests, nations, individuals — we all sin.

- Happily, there is also a path to forgiveness. It’s possible to make up for our sins. To take action — to do something to right our wrongs. The key might be acknowledging the mistake, and marking that acknowledgement with care and an odor that God finds pleasing. Hard to argue with that.

- And it turns out, ignorance doesn’t get you off the hook. If you later realize you did wrong, you still need to make amends.

These are ideas that feel pretty widely accepted today. Sin is universal. But with conscious thought and effort we can move forward.

It’s easy to align these ideas with confession, for example.

I wonder though if they were that widely accepted at the time. As a novel notion, they would be revolutionary.